NOW 22, WHOOP WHOOP. Another year! Still, unfortunately have a vertical license. It doesn't expire until 2016. I can't wait to get my nice horizontal grown-up license.

Andrea, 22 year old Black Feminist. Gender Studies/Africana Studies.

Thursday, February 28, 2013

Sunday, February 24, 2013

Michael Wesch-From Knowledgable to Knowledge-able---Reflection

The quality of light by

which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we

live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives. It

is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and

make it realized. This is poetry as illumination, for it is through poetry that

we give name to those ideas which are, until the poem, nameless and

formless-about to be birthed, but already felt. That distillation of experience

from which true poetry springs births thought as dream births concept, as

feeling births idea, as knowledge births (precedes) understanding.

As we learn to bear the intimacy of scrutiny, and to flourish within it, as we learn to use the products of that scrutiny for power within our living, those fears which rule our lives and form our silences begin to lose their control over us.-Audre Lorde, “Poetry is Not a Luxury”

I’ve chosen to begin with this particular

epigraph, an excerpt from Audre

Lorde’s “Poetry

is Not a Luxury” because I feel it details, in a wondrously poetic fashion,

some of the framework that I will be working from and the perspective I am critiquing

the Wesch text through. Hopefully as you read this post you will more clearly

understand why I’ve chosen this particular Lorde excerpt, but if anything is

unclear in my choice of quotes or anything I bring up throughout this post then

please feel free to ask for clarification and shoot me questions in the comment

section.

|

| Michael Wesch |

built to re-enforce the top-down authoritative knowledge of the teacher…the ‘message’ of this environment is that to learn is to acquire information, that information is scarce and hard to find (that’s why you have to come to this room to get it), that you should trust authority for good information, and that good information is beyond discussion. In short, it tells students to trust authority and follow along (1).

He goes on to note that the new digital age has given people the ability to access knowledge in a new way. In this new way of accessing knowledge they are not simply taking in information that an authority figure is spewing at them but rather they are directly engaging with the information; they are aiding in its creation, its delivery, and everything in between. He argues that knowledge, as it stands now, is not something that can simply be fed to an individual, it is something that must constantly be interacted with and in order to keep up with the way that the digital age has allowed students to engage with information classrooms and teachers must change up their stale authoritarian routine and find ways to “move [their students] from being simply knowledgeable to being knowledge-able” (1). This means that they need to learn how to truly engage with the material, they must be able to critically look at texts and analyze them, not simply memorize ‘important’ facts and reiterate said facts when an exam comes along.

Now, just because I am

able to summarize his general argument (at least in the way that I read the

text) does not mean that I completely agree with the points that he uses. There

were a few moments when I had to disagree with his statements, and other

moments where I felt he was simply not delving deep enough.

Given that Wesch

chooses to use the language of revolution, it is disappointing that he doesn’t

really deliver a deeper analysis of some of the systems that he rails against

and for. One of the dominant discourses of society is that of Individualism. As

the State has gotten more powerful it has worked to eradicate a sense of

community and collectivism amongst people (this is clearly an attempt to stifle

resistance, for no resistance can occur if people cannot develop a collective

consciousness). This idea of individualism and submissiveness (to the State and

those who represent the state i.e: Authority) is taught to us in many ways and

settings, and one of those settings is within the classroom. Wesch notes that

the current teaching methods often rely on the educator being seen as the

authority figure and that all of the students must follow the instructions of

said authority figure very closely. Lecture style classrooms do not breed

community, they breed submission and regurgitated thinking (regurgitated thinking:

we spit back out the same thought/ideas/lessons that we take in. The delivery

will more than likely be in a different order from the original thought digested but the content will be exactly the same). Wesch states that the “Web 2.0”

breeds a “spirit of interactivity, participation, and collaboration” (1) and

that new model classrooms and teaching styles should invoke the same spirit.

Doing so fosters community; it fosters connections between students with their

peers and their professor. It allows knowledge and information to seem more

dynamic instead of static and stagnant. The current teaching methods simply

reenact the same dominator/dominated; authority/submissive narrative. In order

to have a social resistance, whether it is within the classroom or beyond it,

we need to advance beyond the current methods into something that creates a

new, more revolutionary, narrative.

Given that Wesch

chooses to use the language of revolution, it is disappointing that he doesn’t

really deliver a deeper analysis of some of the systems that he rails against

and for. One of the dominant discourses of society is that of Individualism. As

the State has gotten more powerful it has worked to eradicate a sense of

community and collectivism amongst people (this is clearly an attempt to stifle

resistance, for no resistance can occur if people cannot develop a collective

consciousness). This idea of individualism and submissiveness (to the State and

those who represent the state i.e: Authority) is taught to us in many ways and

settings, and one of those settings is within the classroom. Wesch notes that

the current teaching methods often rely on the educator being seen as the

authority figure and that all of the students must follow the instructions of

said authority figure very closely. Lecture style classrooms do not breed

community, they breed submission and regurgitated thinking (regurgitated thinking:

we spit back out the same thought/ideas/lessons that we take in. The delivery

will more than likely be in a different order from the original thought digested but the content will be exactly the same). Wesch states that the “Web 2.0”

breeds a “spirit of interactivity, participation, and collaboration” (1) and

that new model classrooms and teaching styles should invoke the same spirit.

Doing so fosters community; it fosters connections between students with their

peers and their professor. It allows knowledge and information to seem more

dynamic instead of static and stagnant. The current teaching methods simply

reenact the same dominator/dominated; authority/submissive narrative. In order

to have a social resistance, whether it is within the classroom or beyond it,

we need to advance beyond the current methods into something that creates a

new, more revolutionary, narrative.  Throughout the reading

I took issue with Wesch's assertion that within new media we are able to be “creators”

of information, he states this first when he talks about bloggers crating

information (2). I have to strongly disagree with that. We, as bloggers or

writers, are not creating information. We are vessels for information. Blogging

has simply given us a new way to share said information that we have within

ourselves with others. Yes, perhaps we are providing this information in a new

way, but I would be hesitant to say we are “creating” it. We are simply

furthering the path of information. What we are creating…what we are producing…is thought. Thought based on

the information that we have collected, but we are not creating information

itself. We are compiling the information and turning it into something. On a

similar note, I did not appreciate Wesch’s argument that “our old assumption

that information is hard to find, is trumped by the realization that if we set

up our hyper-network effectively, information can find us” (2). He then goes on

to use an example of a web app that I have never heard of, which feeds into my

opinion that his argument comes from a place of privilege. I could make the

argument that within academia there is SO much information, it seems limitless

and like it is constantly coming at me. However, to say that statement and that

statement alone would be ignoring the fact that academic information is hard to

find for some people. Web information, even with the ubiquity if the internet,

can be hard to find. Some people do not know what to look for, where to

explore, or what to explore. The question becomes: How do we share our

knowledge with a wider audience? Simply putting it online is not enough. How do

we cultivate the appropriate audience? What even is the appropriate audience?

If we limit it to fellow academics like ourselves then are we simply moving the

traditional classroom onto the internet? And if we choose to broaden our

audience base how do we ensure that we get as many people as we can, and how do

we guarantee that we are actively engaging with them?

Throughout the reading

I took issue with Wesch's assertion that within new media we are able to be “creators”

of information, he states this first when he talks about bloggers crating

information (2). I have to strongly disagree with that. We, as bloggers or

writers, are not creating information. We are vessels for information. Blogging

has simply given us a new way to share said information that we have within

ourselves with others. Yes, perhaps we are providing this information in a new

way, but I would be hesitant to say we are “creating” it. We are simply

furthering the path of information. What we are creating…what we are producing…is thought. Thought based on

the information that we have collected, but we are not creating information

itself. We are compiling the information and turning it into something. On a

similar note, I did not appreciate Wesch’s argument that “our old assumption

that information is hard to find, is trumped by the realization that if we set

up our hyper-network effectively, information can find us” (2). He then goes on

to use an example of a web app that I have never heard of, which feeds into my

opinion that his argument comes from a place of privilege. I could make the

argument that within academia there is SO much information, it seems limitless

and like it is constantly coming at me. However, to say that statement and that

statement alone would be ignoring the fact that academic information is hard to

find for some people. Web information, even with the ubiquity if the internet,

can be hard to find. Some people do not know what to look for, where to

explore, or what to explore. The question becomes: How do we share our

knowledge with a wider audience? Simply putting it online is not enough. How do

we cultivate the appropriate audience? What even is the appropriate audience?

If we limit it to fellow academics like ourselves then are we simply moving the

traditional classroom onto the internet? And if we choose to broaden our

audience base how do we ensure that we get as many people as we can, and how do

we guarantee that we are actively engaging with them?

A bit later Wesch

discusses the idea of the “crisis of significance”. He states that we need to “bring

relevance back to education” (2). I would argue that we would first have to

define what education is. And this is not only the job of the educator but also

the job of the person being ‘educated’. Why do they want to be ‘educated’? What

do they see ‘education’ as? What is the goal of their ‘education’? For me,

education for liberation is my goal. Therefore, the types of knowledge that

catch my attention are most of the things that I can find applicable to

resistance, resistance mobilizations/theory, forms of resistance, and

foundational to revolutionary action. This framework makes many concepts quite significant, even if it doesn't seem so at first.

To use this class as an example, learning about

media as a medium for ideology is critical for me, as I must be able to see

all of the ways that the ruling/dominant class works to manipulate and further

repress others. If I cannot see how they are working against us, how could I

possible begin to address ways in which to dismantle the system/structure? I

think that it is our duties as students, as active engagers with knowledge, to

question what our guiding framework is and what our goal is. Are you simply learning

in order to eventually get a career? If so, why is that? What has taught you

that in order to be ‘complete’ you need to learn things that may mean nothing

to you in order to be in a job that also may mean nothing to you in order to

earn a paycheck? There’s not necessarily anything wrong with that, what’s wrong (or perhaps "problematic" would be a better word) is following a narrative that has been written for you without ever stopping to

question what the narrative is and why you feel the need to follow it. We must

all develop a working framework for how we seek and ingest

knowledge/information.

Because this post is

plenty long enough I will attempt to wrap it up by addressing Wesch’s “Not

Subjects but Subjectivities” section while incorporating another quote from the

magnificent Audre Lorde. This is, perhaps, the section that I had the least

complaints about (other than my overarching complaint that Wesch does not delve

as deeply into some of these concepts as he could/should). Wesch states that “learning

a new subjectivity [ways of approaching, understanding, and interacting with the

world] is often painful…You have to unlearn perspectives that may have become

central to your sense of self” (3). How could I note read this as “DECOLONIZE/LIBERATE

YOUR MIND!”?? Our knowledge, our current subjectivity, is not our own. It is

the dominant society’s knowledge/subjectivity. We are often taught frameworks

that do not allow us to further analyze our surroundings, at least not in ways

that would allow us to truly QUESTION, TRANSFORM, and RESIST. At the end of her

poem But What Can You Teach My Daughter

Lorde states that “even my daughter…knows/what you know/can hurt/but what you

do/not know/can kill”. We need to teach that!

This should be our working framework! If this were our framework then would we

not all be interested in gathering as much knowledge as possible and engaging

with it as much as we can? If we acknowledged the fact that the knowledge that

we allow to slip through our fingers could prove fatal (be it literally or metaphorically

in the sense of social or civic death), then we would try our hardest to take

in as much as we could, and not only that, but we would try to understand it

and work with it to the best of our abilities? And with the more knowledge that

we take in, the more that we develop our working frameworks for

life/knowledge-gathering, the more successful we will be at dismantling the

system that works to oppress/repress/suppress us!

To try and put my questions and comments into one section would be

impossible! My questions for the class are strewn throughout this post. I

suppose my biggest question(s) for the class would be: what is your guiding

framework for knowledge-intake? What is your

goal when it comes to education? How often do you question the goals that you

have that seem to be natural to you?

And, because I love this poem so darn much, I will end this post with

it.

But

What Can You Teach My Daughter

What do you mean

no no no no

you don’t have the right

to know

how often

have we built each other

as shelters

against the cold

and even my daughter knows

what you know

can hurt you

she says her nos

and it hurts

she says

when she talks of liberation

she means freedom

from that pain

she knows

what you know

can hurt

but what you do

not know

can kill.

Works Cited

Lorde, Audre. The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde. New York: Norton, 1997. Print.

Lorde, Audre. "Poetry Is Not a Luxury." Power, Oppression and the Politics of Culture: A Lesbian/Feminist Perspective. Web. 24 Feb. 2013.

Wesch, Michael. "From Knowledgable to Knowledge-able: Learning in New Media Environments." Academic Commons. Web. 24 Feb. 2013.

First image found here

Second image found here

Third image found here

Saturday, February 23, 2013

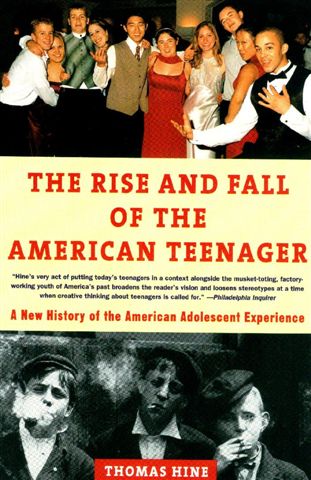

Thomas Hines-The Rise and Fall of the American Teenager: Quotes/Reflection

Because I have merged the format of Quotes and Reflection I have chosen

to work with only two quotes so that I may explore them more in depth while

still maintaining a reasonable word count.

’Maybe I’m something special, and

maybe I’m not. Maybe I’m here for a reason and I might be going somewhere after

this, but then again I might not. I wonder where I fit in?”…Figuring out where

they fit in—to the universe, the world, the economy, their social circle, their

family, is a project on which teenagers spend a lot of their time and energy…study

after study suggests that teenagers’ principal preoccupation is to adapt, to

find a place in life. (2)

Thomas Hines, in his introduction

to The Rise and Fall of the American

Teenager, quotes his younger, seemingly angstier, self as a way to

personally connect with the studies that he alludes to (these studies that talk

about how teenagers are constantly on a quest to “find themselves”). He does so

not to prove that these students are right

but rather to highlight ways in which our teenage self isn’t a completely

different entity from our grown-up self. This is the same idea that we address

with our third course assumption: Teenagers are not some alien life form.

On a personal level, the thoughts

that Hines quotes from his younger self are thoughts that are constantly

running through my mind. I am always wondering what the goal of my existence

is, if I will become “something” if I will “be somebody”. The fact that these

thoughts are constantly running through my head does not expose me to be

stunted but rather it shows that I am human. I am a human who has grown up in

this Western society. Let’s take a look at some of the “greatest” writers (I

put “greatest” in quotes because there is always a question of how and why some

authors are canonized and others are not, but that is not a relevant train of

thought for this post) and philosophers: are not most, if not all, of them in

some sort of perpetual

existential crisis? Are these

thoughts that Hines quotes not the thoughts that run/ran through their head

constantly and served as major themes for their work? And yet somehow we have

decided that it is only teenagers who are on a quest to find themselves when,

in reality, we are all on the same quest.

We live in an individualistic society, which not only means that we lack a

sense of community with each other; it also means that we see ourselves as

individual, independent, beings with personality and thoughts that mean

something. Given that we identify ourselves as individuals first and community

members second (or never) we, of course, are then always trying to figure out

just who exactly we are. This is not a teenager crisis, it’s a human crisis.

On a personal level, the thoughts

that Hines quotes from his younger self are thoughts that are constantly

running through my mind. I am always wondering what the goal of my existence

is, if I will become “something” if I will “be somebody”. The fact that these

thoughts are constantly running through my head does not expose me to be

stunted but rather it shows that I am human. I am a human who has grown up in

this Western society. Let’s take a look at some of the “greatest” writers (I

put “greatest” in quotes because there is always a question of how and why some

authors are canonized and others are not, but that is not a relevant train of

thought for this post) and philosophers: are not most, if not all, of them in

some sort of perpetual

existential crisis? Are these

thoughts that Hines quotes not the thoughts that run/ran through their head

constantly and served as major themes for their work? And yet somehow we have

decided that it is only teenagers who are on a quest to find themselves when,

in reality, we are all on the same quest.

We live in an individualistic society, which not only means that we lack a

sense of community with each other; it also means that we see ourselves as

individual, independent, beings with personality and thoughts that mean

something. Given that we identify ourselves as individuals first and community

members second (or never) we, of course, are then always trying to figure out

just who exactly we are. This is not a teenager crisis, it’s a human crisis.

This lengthy waiting

period has tended to reduce young people’s contacts with older people and

increase them with people who are exactly the same age. That, in turn, has led to

the rise of a youth subculture that has helped define and elaborate what it

means to be a teenager (7).

The lengthy waiting period Hines

is talking about is the “long period of education, exploration, and deferred

responsibility” (7). Teenagers are in school longer than their predecessors

(or, rather, their predecessors’ predecessors); they are less likely to be

expected to work, and generally when they do work they are employed at places

that aim to hire teenagers; and they are expected to be on the aforementioned

existential journey to find themselves. All of these factors lead to less

cross-over with non-teenagers and so teens are often surrounded by their peers, resulting in "youth subculture".

Now,

just because I can summarize Hines’ argument does not mean I agree with it

fully. This point of his is perhaps the point that makes it the most obvious

that his usage of teenager actually means middle-class White teenager.

Depending on one’s social class and situation it should not be expected that

they 1) will not be working and 2) will have less interaction with those older

than themselves. This does not take in account the families who live in a

household with multiple generations (and thus are not only spending time with

people a bit older than themselves but with those who are FAR greater in age).

A teenager who has to help support the family does not have the luxury to only

choose a job that allows them to essentially shoot the breeze with other teens.

They will be on the hunt for a job that best suits their needs and their

schedules, regardless of the age and life circumstance of their co-workers. And

having to be a pillar of support for the household tends to mean lots of work

hours, and if this teen is a good student then they certainly do not have all

that much time to spend hanging out with other teens. Free time is a luxury for

many teenagers. I’m not saying that what Hines posits is wrong but rather that it just does not take enough different

factors into account. He should have made a disclaimer or made a less

generalizing claim, but because he did I feel that it is our duty to take him

to task for that (even if it is simply on our blogs and in class). In general,

in class I would like to further discuss the ways in which Hines makes it clear

that the “teens” he talks are about are middle class White teens. Middle class

White teenagers is a shrinking group, there is no reason why texts should still

use them as a norm, and no reason why we should accept that norm willingly.

On a personal

level, I have to wonder if some of these things are why I often feel a bit of a

disconnect with my peers. I’ve been working since I was 13 and had 3 jobs at

the age of 15. Due to various personal life circumstances I did not have the “typical”

(again, what is “typical”, really?) teenage experience. This idea of the “teen

subculture” is so prevalent that those who existed outside of said subculture

are at a bit of a loss with their peers. That doesn’t make those of us who had

different teenage experiences any less of a “teenager”, it simply means we didn’t

have the expected teenage life. And in these changing times, how many people are

actually having the expected teenage experience? What is the “teenage

subculture” truly? Can we simply give it such a general name when the

subculture may vary by race, region, etc? And, by implying that there is a

shared “teenage experience” aren’t we furthering the feelings of confusion,

angst, un-belonging, for those teenagers who exist outside of said experience?

Sunday, February 10, 2013

A Tangle of Discourse: Girls Negotiating Adolescence--Quotes

When addressing the weaknesses of the discursive framework

that Rebecca C. Raby sets forth in “A Tangle of Discourse: Girls Negotiating Adolescence” she notes that “Discourses are deployed unevenly

between adolescents of differing social locations…Similarly, discursive effects are unequal. In particular, the

surveillance and regulation of youth is significantly affected by gender,

class, and race.”(426) This quote is taken from the beginning of the text, and

it is where Raby is noting some of the problems of her own study and studies

like hers as well as explaining her decisions in how she conducted her study.

Raby notes these caveats so that they are made clear, but she doesn’t take them

into account for her own study (which she herself recognizes in the same

paragraph as the above excerpt). It is completely understandable for Raby to “set

[gender, class, and race] aside in [the] paper” (426); the scope of her study

could not incorporate a section on the intersections of gender, class, and race

with adolescence. It is unfortunate, however, because there would surely be

some enlightening results had she been able to incorporate and elaborate on

such an intersection. For example, the way in which young Black/Latino boys are

perceived compared to young White males would be quite interesting,

particularly when discussing the carceral nature of the surveillance as it applies

to these young men.

In her section “Discourses of Adolescence” Raby shares the definition of discourse that she is working with. Raby elaborates upon the concept of discourse that Vivian Burr defines in An Introduction to Social Construction:

In her section “Discourses of Adolescence” Raby shares the definition of discourse that she is working with. Raby elaborates upon the concept of discourse that Vivian Burr defines in An Introduction to Social Construction:

Discourses

organize how we think, what we know and how we can speak about the world around

us. Vivian Burr notes ‘A discourse refers to a set of meanings, metaphors,

representations, images, stories, statements and so on that in some way together

produce a particular version of events’…Privileging one set of representations

over another, discourses tend to claim the status of truth. We are always

embedded in discourses. As such, and as discourses work as truth statements, it

is difficult to ‘see through’ them to identify how our reality is shaped. (430)

It is important that the reader understands the way in which

Raby is using “discourse” because the entire study is built upon the idea of

discursive frameworks about adolescents/ce and the way in which adolescents

interact with the framework. The definition should seem really familiar to us by now,

as it could also be applied to “ideologies”. I posit that the dominant ideologies

of society work to create the dominant discourses. We see this in Raby’s own

study. For example: Capitalism is an obvious dominant ideology in our society;

unsurprisingly, “pleasure consumption” is a dominant discourse of adolescence

that Raby identifies. Our consumer culture has been able to manipulate

teenagers in a variety of ways. Raby notes that “self-expression and identifications

are intricately expressed through certain types of fashion…and body adornment”

(437). This is a wonderful example of how the various discourses interact with

one another. Rebellion and finding oneself as an individual has become

naturalized (these are the discourses Raby labels as “the storm” and “becoming”)

to a point these things seem inherent to adolescence. Consumer culture markets

specifically towards teenagers, telling them that they can find themselves at

the local mall. Telling them that makeup, or certain fashions, will help them

make a statement to the world. In order to fulfill the “need” to rebel/express

oneself many teens fall prey to the manipulation of consumer culture. This is

the pleasurable consumption. It is pleasurable because it fulfills what is

perceived as an innate desire.

It is important that the reader understands the way in which

Raby is using “discourse” because the entire study is built upon the idea of

discursive frameworks about adolescents/ce and the way in which adolescents

interact with the framework. The definition should seem really familiar to us by now,

as it could also be applied to “ideologies”. I posit that the dominant ideologies

of society work to create the dominant discourses. We see this in Raby’s own

study. For example: Capitalism is an obvious dominant ideology in our society;

unsurprisingly, “pleasure consumption” is a dominant discourse of adolescence

that Raby identifies. Our consumer culture has been able to manipulate

teenagers in a variety of ways. Raby notes that “self-expression and identifications

are intricately expressed through certain types of fashion…and body adornment”

(437). This is a wonderful example of how the various discourses interact with

one another. Rebellion and finding oneself as an individual has become

naturalized (these are the discourses Raby labels as “the storm” and “becoming”)

to a point these things seem inherent to adolescence. Consumer culture markets

specifically towards teenagers, telling them that they can find themselves at

the local mall. Telling them that makeup, or certain fashions, will help them

make a statement to the world. In order to fulfill the “need” to rebel/express

oneself many teens fall prey to the manipulation of consumer culture. This is

the pleasurable consumption. It is pleasurable because it fulfills what is

perceived as an innate desire. Perhaps the most interesting part of Raby’s study, which unfortunately she did not spend much time on, was the ways in which the teens she studied not only accepted but actively engaged with the dominant idea of what a “teenager” is. Raby noted that “the teens that I interviewed had such difficulty negotiating their occupation and rejection of the category ‘teenager’…All of them easily cited negative stereotypes about teens…Often the young women would cite several negative stereotypes about teenagers, then distance themselves and their friends, often through the separation of ‘good’ teens from the ‘bad’ ones” (441). I find this particularly interesting because this seems to be a common practice in many subjugated groups (as Raby calls teens. Whether or not they can truly be considered a subjugated group is up for debate). It isn’t uncommon to have conflicted People of Color distance themselves from other POC, noting that they aren’t like “those other ____ folk” or people from lower classes using others as an example of what they are not/will never be (see half of the conversation surrounding Honey Boo Boo) These teenagers are both accepting and rejecting the dominant idea of what a “teenager” is. They view themselves as exceptions to the stereotype instead of really reflecting on the fact that perhaps the stereotypes themselves are flawed. I will use a PSA I found on Youtube to close this post.

It was made by a youth

coalition, which is important to note. Because it was made by a youth coalition

it seems like it would not be a ridiculous to assume that the teens had a lot

of input on the direction of the video. Now, with that in mind, take a close

look at the teen who wants beer. She is at once othered by her piercings and

desire to drink beer and yet also very much “in line” because of those desires.

The other teenagers are exceptions to the dominant stereotypes, look how clean

cut they are! And they love root-beer ‘cause beer is totally uncool. It is interesting that these youth chose to make

the “bad apple” a girl with obvious physical forms of “self-expression” and “rebellion”

(the piercings). It’s clear that in this moment the youth coalition bought into

the dominant discourses of what a rebellious teenager is/looks like/desires.

Questions and Comments:

During the week I would like to discuss ways in which our mainstream media, particularly television shows and films aimed at teenagers, works to naturalize the discourses that Raby identifies. We should keep in mind that many of these shows 'about teen lives' are created by adults. Keeping that in mind will certainly lead to interesting analyses of popular representations of teenagers in media today.

Works Cited

Header image found here

Discourse image found here

Raby, Rebecca C. "A Tangle of Discourses: Girls Negotiating Adolescence." Journal of Youth Studies 5.4 (2002): 425-48. Web.

Thursday, February 7, 2013

Faces of Addiction

I stumbled upon an amazing photostream today, it's called Faces of Addiction. Really powerful images. Here's the photographer's description of the album:

"The stories of addicts in the Hunts Point neighborhood, the poorest in all of New York City. I post people's stories as they tell them to me. What I am hoping to do, by allowing my subjects to share their dreams and burdens with the viewer and by photographing them with respect, is to show that everyone, regardless of their station in life, is as valid as anyone else. Its easy to ignore others. By not looking, by not talking to them, we can fall into constructing our own narrative that affirms our limited world view. "

Great piece, if you haven't checked it out yet please do so. And explore his other photostreams.

"The stories of addicts in the Hunts Point neighborhood, the poorest in all of New York City. I post people's stories as they tell them to me. What I am hoping to do, by allowing my subjects to share their dreams and burdens with the viewer and by photographing them with respect, is to show that everyone, regardless of their station in life, is as valid as anyone else. Its easy to ignore others. By not looking, by not talking to them, we can fall into constructing our own narrative that affirms our limited world view. "

Great piece, if you haven't checked it out yet please do so. And explore his other photostreams.

Tuesday, February 5, 2013

Birthing While Black from My Brown Baby

Just saw this article making the rounds on tumblr and it made me think about the reading and some of the blog responses people have put up. This woman's account, and the many Black women she represents, certainly sheds a light on why it's so difficult for Black women and girls to see themselves as princesses. Even when they have the money for "royal treatment" they are often still treated like garbage. This is why I'm not 100% against some race-bending fairy tales. I want more Black princess stories out there because society often treats Black women like they can amount to nothing more than maids/servers (unless of course they are the lucky few to be RICH and FAMOUS. But, that's a whole different conversation that would involve a lot about pigmentocracy and White standards of beauty because...well take a gander at the richest and most famous Black women, many of them very much fall in line with the general aesthetic that is accepted by the mainstream).

From the article

From the article

Despite an incredible birthing experience facilitated by my personal angel/ob-gyn, from almost the moment my baby took her first breath, her mother was treated like a 14-year-old drug-addicted welfare queen, there to push out yet another daddy-less baby. Seriously.

- They tested my newborn for drugs (though I’ve never taken an illicit substance in my entire life) without my consent—something I later found out hospitals do at disproportionately higher rates with black babies than white ones.

- Despite that I paid for the private room and meals, I was immediately put in a massive post-birth room with three other women and their newborns. I was moved only after I asked why I wasn’t in a private room—a question that elicited scowls and foot-dragging from the nurse until she bothered to check my paperwork to see that, indeed, I’d paid for a private room. It took three hours for my room to be changed.

- Once in the private room, the nurses disappeared for nine hours! Seriously.Nine.I had no diapers. No idea how to breastfeed properly (and no bottle or milk to feed my baby if I chose to formula feed). No instructions on what to do to care for my post-birth body (was it okay to walk? Pee? Wash?). Nothing. I seriously thought I was being punished for asking (nicely) for what I’d paid for. When a nurse finally did show up, she came with a “gift bag” full of Similac and coupons for… Similac.

- The private “suite” was disgusting. The bathroom smelled like cheap, potent cleaning chemicals. The shower tiles were grimy and the shower curtain was full of mold. There wasn’t so much as a picture on the bland walls. (I begged my back-up ob-gyn to let me go home after one night; thank God, she signed off on it.)

- The nursing staff was genuinely surprised (!) that the guy by my side, Nick, was my husband—and actually said that stupid ish out loud.

- Our special meal arrived only after we pointed out to the nurses that the fees we paid included it, and by the time it got to us, our dinner was cold and our champagne (a tiny hand-held bottle we could have finished with one big sip from the straw) was warm.

I couldn’t get out of that place fast enough. And when it came time for me to have my second child, I stayed far, far away from that hospital—even changed my ob-gyn, which really broke my heart to do—to avoid it like the damn plague.

I wondered then what I know to be true now: It didn’t matter how much money I had in my bank account or how good my insurance was, or that I had a ring on my finger, or that I was smart and accomplished, or that I tried to pay my way out of substandard service. At the end of the day, to almost everyone in that hospital, I was just another black girl pushing out another black baby and neither of us deserved to be treated with dignity or respect, much less special. That human beings charged with caring for new life and the people who ushered in that miracle could traffic in this kind of reprehensible treatment of anyone, much less a new mother—no matter her race, financial or marital status, or background—is beyond my level of comprehension.

Saturday, February 2, 2013

Unlearning the Myths That Bind Us-Reflection

In “Unlearning

the Myths That Bind Us” (from Rethinking

Our Classrooms) Linda Christensen discusses the ways in which children’s

stories, be they in the form of cartoons; fairy-tales; or films; work to, somewhat

insidiously, pass on society’s dominant ideologies. She also describes the way

in which her classes have dealt with the idea of children’s stories as a way to

teach children how to behave in-line with societal expectations. There was

nothing surprising in this reading for me, as I’ve been pretty aware of the

ways in which our media, whether directed at adults or children, works to try

and create conformists of us all. However, it was refreshing to read the ways

in which Christensen’s students attempted to take direct action against this “secret

education” (126).

One of

Christensen’s students noted that “when we read children’s books, we aren’t

just reading cute little stories; we are discovering the tools with which a

young society is manipulated” (126). Omar hits the nail right on the head;

taking a critical eye to stories and media aimed at children can prove to be

very enlightening (and disheartening). Take, for example, one of the morals

that Perrault offers for the classic fairy tale Little Red Ridinghood (the story, as well as the entire Norton

collection of The Classic Fairy Tales

can be found here):

From this story one learns that children,

Especially young

girls,

pretty, well-bred,

and genteel,

Are wrong to

listen to just anyone,

And it’s not at

all strange,

If a wolf ends up

eating them.

I say a wolf, but

not all wolves

Are exactly the

same.

Some are perfectly

charming,

Not Loud, brutal,

or angry,

But tame,

pleasant, and gentle,

Following young

ladies,

Right into their

homes, into their chambers,

But watch out if

you haven’t learned that tame wolves

Are the most

dangerous of all.

Perrault’s version of Little Red Riding is an incredibly

common, and still told, version of the fairy-tale. This moral, a moral told

to young children at the tail-end of a story meant to soothe them to sleep, not

only perpetuates the idea that women must constantly be ever vigilant of men

lest they get ‘eaten’ (also known as raped. Or, perhaps, even simply sexed

before marriage) but it also highlights one of the (many) ways in which patriarchy is

harmful to men as well as women. It

depicts all men as being beholden to their carnal nature; it makes it sound

like men are unable to control themselves and that they are inherently animalistic

so all women just need to beware. This is a harmful idea to disperse not only

because it feeds directly into our modern rape culture but also because it’s an

incredibly insulting (and untrue) portrayal of men. It makes it seem as if all

men are potential rapists (wolves) because they just cannot help themselves. Now Little

Red doesn't seem all that much like a “cute little story” does it? And it didn't even take the most critical eye to see the problem with this moral, it just

took a mind open to questioning things that we've been taught to be comfortable

with.

Perrault’s version of Little Red Riding is an incredibly

common, and still told, version of the fairy-tale. This moral, a moral told

to young children at the tail-end of a story meant to soothe them to sleep, not

only perpetuates the idea that women must constantly be ever vigilant of men

lest they get ‘eaten’ (also known as raped. Or, perhaps, even simply sexed

before marriage) but it also highlights one of the (many) ways in which patriarchy is

harmful to men as well as women. It

depicts all men as being beholden to their carnal nature; it makes it sound

like men are unable to control themselves and that they are inherently animalistic

so all women just need to beware. This is a harmful idea to disperse not only

because it feeds directly into our modern rape culture but also because it’s an

incredibly insulting (and untrue) portrayal of men. It makes it seem as if all

men are potential rapists (wolves) because they just cannot help themselves. Now Little

Red doesn't seem all that much like a “cute little story” does it? And it didn't even take the most critical eye to see the problem with this moral, it just

took a mind open to questioning things that we've been taught to be comfortable

with.

Christensen

spends some time addressing stereotypes, their prevalence in children’s

stories, and the ways in which they are harmful. She states that “the

stereotypes and worldview embedded in the stories become accepted knowledge”

(127). This idea, coupled with her earlier quote from Beverly Tatum (“cartoon

images…were cited by the children…as their number one source of information”)

is particularly troubling when we take a look at many of the cartoons that our

society’s children are watching. There’s no getting away from the racism and sexism that is

prevalent in children’s media. Jafar, from Aladdin,

a somewhat recent Disney film, is portrayed as far darker and more “ethnic”

looking than the ‘good’ characters from the film. Whether or not that is a

coincidence (which is doubtful), the message it sends is that ethnic=bad (as

well as ugly and old=bad, which we also get from Ursula in The Little Mermaid, the crone from Snow White, the list could go on).

The stereotypes

don’t stop once the images are no longer being targeted at children. Media is

constantly pushing the dominant ideology on its consumers, whether the consumer

is 3 or 33. This serves to ensure that the values that have been subliminally

taken in stick with us. We have to be constantly bombarded with these

problematic images otherwise we are more likely to hit that pane of glass in

the river (for those that missed class on Thursday this reference may be indiscernible, shoot me

a message and I’ll clarify for you!). Let’s

use the past Black female Academy Award winners for example. All of these women

were in films for adults. And they all portrayed common stereotypes of

Black women. Halle Berry, the only Black

woman to have won an Oscar, won for Monster’s Ball in 2001 for playing Leticia

Musgrove, a character that very much fits the common Black trope of the “Jezebel”.

Five Black women have won Academy Awards for supporting roles. The first was

Hattie McDaniel for playing the quintessential Mammy (known as…Mammy) in Gone with the Wind. Whoopi Goldberg won

her Oscar for playing a Magical Nigress in Ghost.

Jennifer Hudson was the overweight Black Diva in Dreamgirls (arguably the least

offensive trope to have won an Oscar). Mo’Nique won her Oscar for her portrayal

of Mary Lee Johnston in Precious;

Mary Lee was an abusive, “welfare queen” who was a parasite not just on the

system but also her daughter. And lastly to bookend the list we have the most

recent Black Academy Award winner: Octavia Spencer for her role as

The stereotypes

don’t stop once the images are no longer being targeted at children. Media is

constantly pushing the dominant ideology on its consumers, whether the consumer

is 3 or 33. This serves to ensure that the values that have been subliminally

taken in stick with us. We have to be constantly bombarded with these

problematic images otherwise we are more likely to hit that pane of glass in

the river (for those that missed class on Thursday this reference may be indiscernible, shoot me

a message and I’ll clarify for you!). Let’s

use the past Black female Academy Award winners for example. All of these women

were in films for adults. And they all portrayed common stereotypes of

Black women. Halle Berry, the only Black

woman to have won an Oscar, won for Monster’s Ball in 2001 for playing Leticia

Musgrove, a character that very much fits the common Black trope of the “Jezebel”.

Five Black women have won Academy Awards for supporting roles. The first was

Hattie McDaniel for playing the quintessential Mammy (known as…Mammy) in Gone with the Wind. Whoopi Goldberg won

her Oscar for playing a Magical Nigress in Ghost.

Jennifer Hudson was the overweight Black Diva in Dreamgirls (arguably the least

offensive trope to have won an Oscar). Mo’Nique won her Oscar for her portrayal

of Mary Lee Johnston in Precious;

Mary Lee was an abusive, “welfare queen” who was a parasite not just on the

system but also her daughter. And lastly to bookend the list we have the most

recent Black Academy Award winner: Octavia Spencer for her role as

In class next week

(or perhaps in the comment section of this post) I would like to find

out what stories/shows/movies my peers once loved (or still love) that, upon

critical analysis, they see as being incredibly problematic and simply stories

that are acting as mediums for the dominant society’s message. Me first: I love Mulan, but unfortunately there is plenty of sexism and problematic racial portrayals in that film. I still will break out in song anytime someone says "Let's get down to business", but I no longer love that film unquestioningly. Furthermore, I’d

like to talk about ways in which people feel like we can take direct action and

work to counteract the messages that are being forced down our children’s

throats. Christensen’s class did some interesting work, I’d like to see how we

can further build upon what we've read in the text.

Works Cited

Christensen,

Linda. "Unlearning the Myths That Bind Us." Rethinking Our Classrooms: Teaching for

Equity and Justice / [editors ... Bill Bigelow ... Et Al.]. By Bill Bigelow, Linda Christensen, and

Stan Karp. Milwaukee, WI: Rethinking Schools, 2007. 126-37. Print.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)